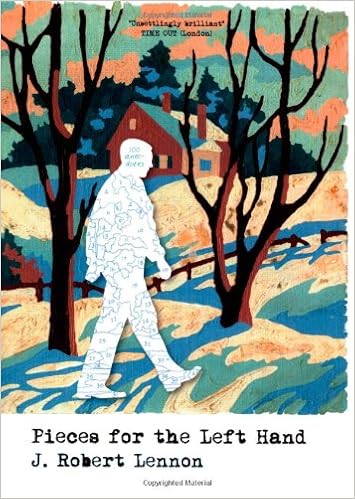

Pieces for the Left Hand by J. Robert Lennon

Graywolf’s 2009 reissue of J. Robert Lennon’s collection of literary anecdotes, Pieces for the Left Hand, seems to have found its niche as one of those hushed recommendations pressed reverently among writers working in short form. In fact, this review was delayed while I waited for the return of my copy from a writer who had brought it out of state for the holidays. I don’t blame him. With each piece rarely longer than two pages, it’s an agreeable travel companion. More importantly, though, the stories strike that animating spark writers seek in their reading selections: they make you want to write. These quirky, luminous pieces remind us how much of the vast material of experience can be fashioned into fiction. They explore narrative possibilities, act as launch pads, springboards for the imagination. While Lennon may be better known for more structurally conventional novels—Mailman (2003) and Happyland (2013), which made a lot of press for its serialization in Harper’s Magazine—Pieces for the Left Hand earns its place on the shelf beside contemporary short form classics like David Markson’s essayistic montages and Thomas Bernhard’s The Voice Imitator.

Graywolf’s 2009 reissue of J. Robert Lennon’s collection of literary anecdotes, Pieces for the Left Hand, seems to have found its niche as one of those hushed recommendations pressed reverently among writers working in short form. In fact, this review was delayed while I waited for the return of my copy from a writer who had brought it out of state for the holidays. I don’t blame him. With each piece rarely longer than two pages, it’s an agreeable travel companion. More importantly, though, the stories strike that animating spark writers seek in their reading selections: they make you want to write. These quirky, luminous pieces remind us how much of the vast material of experience can be fashioned into fiction. They explore narrative possibilities, act as launch pads, springboards for the imagination. While Lennon may be better known for more structurally conventional novels—Mailman (2003) and Happyland (2013), which made a lot of press for its serialization in Harper’s Magazine—Pieces for the Left Hand earns its place on the shelf beside contemporary short form classics like David Markson’s essayistic montages and Thomas Bernhard’s The Voice Imitator.

Lennon’s collection situates itself as a writer’s journal—even its size and design suggest an arty Moleskine notebook. The introduction, in third person, suggests that the anecdotes that follow result from the author’s ambles through the pastoral countryside of small town Upstate, New York:

Every day, for months, he sifted through the growing pile of memories, until he had begun to tell them to himself, as stories. I once knew a man, the stories began. A woman I know. In our town.

Many anecdotes share this tone, the wry nonchalance of overheard stories, conversations, bizarre coincidence, and the curios of the local news section, many bearing conspicuous relation to news events and geography of Ithaca, New York, where Lennon lives and teaches.

The book’s 100 anecdotes are loosely grouped into themed sections, each opening with a micro-narrative that establishes the tone, such as the opening to the section titled “Parents and Children”:

When my wife was pregnant with each of our children, I imagined clearly their future appearance and demeanor. It was young men that I imagined, but my wife gave birth to daughters. Today, when I see my grown daughters, I often have the strong but incorrect impression that I have someone I would like them to meet, and realize that it is the imaginary men I thought they might become to whom I want to introduce them, and with whom I believe they would really hit it off.

Whether isolating a fleeting glitch of thought or chronicling a university’s sabotaged plan to cool its buildings with lake-bottom water, Lennon’s gentle nudging of credible premises often reveals the compromised architecture of narratives generally as well as the profound strangeness inside the humdrum heart of life. Still, many of these one-page narratives manage to achieve startling moments of beauty. A group of foreign tourists in “Twilight” asks for directions to the toilet, which the narrator mishears as “twilight,” and so directs the tourists to the best place for watching sunsets—a lakeside pier, where “a marvelous palette of colors would be cast onto the bottoms of the clouds and reflected on the water below.” The confusion is resolved when a more skilled speaker steps forward. Yet later in the evening, as the narrator walks home, he sees the same group of tourists standing at the pier’s end, watching the prescribed sunset. Readers share something in common with these tourists. Lennon focuses our perspective in unexpected directions and, at his best, catches us wonderstruck by the reflections cast between these splintered stories.

Just as often, however, the complexity of a piece folds in on itself. A character confronting a multifaceted reality becomes a meditation on the cognitive process of determining which reality to choose. Years after moving to a new town, the main character in “Switch” discovers that his cat’s nameplate is engraved with another cat’s name. Additionally, the listed address hails from the same neighborhood where he lived before the move. Confronted with this mildly disturbing anomaly, he has to decide which version of reality is more plausible:

I realized how very unlikely a prank the switching of collars was; and simultaneously I began to recall changes in our cat’s personality around the time of our move which, quite naturally, we assumed to be consequences of the move itself, but which now suddenly seemed like the consequences of his not being our cat.

One of the greatest pleasures of these stories is the invitation to turn inward with them. They’re not considerations about what one would do—in the case of the above cat, for example—but meditations on how one concludes anything about one’s reality, how it’s shaped by one’s motives, desires, fears, and the difficulty of delineating these influences at all. The left-handedness of Lennon’s anecdotes reveals itself in the practiced dexterity of crafting stories with this double-edged ambiguity.

In the way of craft, there’s everything to admire. Personally, I kept returning to Lennon’s last sentences. In “Coupon,” a comatose mother wills herself back to health after overhearing a tender exchange between her daughter and son in the hospital room. The siblings decide not to tell her that the conversation she later described never occurred. Later, after the mother has died of unrelated causes, the son happens upon a detergent commercial in which the dialogue bears uncanny resemblance to the exchange the mother attributed to him and his sister. The anecdote might have ended here, with the droll realization that she’d appropriated this curative dialogue from the hospital television set. But the virtue of Lennon’s endings are their avoidance of tidy narrative twists in favor of spare slack for readers to knot themselves: “I promptly wrote a letter to the detergent company, telling them the entire story. Not long afterward I received a coupon for a free box of detergent. No other reply was provided.”

Here are some final sentences I returned to more than once: “For some time now, townspeople have been reluctant to take anything at other than face value.”

“Our friend takes a perverse pleasure, he tells us, in dropping these people off at an inconvenient place, such as over a steaming subway grate or directly in front of a street vendor.”

“This suits us well, however, as it seems possible that our friend, if given the opportunity, might kill us.”

It seems excessive, even in a review, to reduce these stories to summaries. They’ve already been condensed to their maximum potency. Lennon, too, is conscious of the writer’s obsession with abbreviation in the collection’s final piece, “Brevity,” about a novelist consumed with revising her 1,000page novel. She hacks away until the novel becomes a novella, a short story, a paragraph, a sentence, and finally a haiku: “Tiny Upstate town / Undergoes many changes / Nonetheless endures.” It’s a summary broad enough to suit the collection it concludes. Thankfully, though, Lennon knows exactly how to scale his anecdotes, to distill their complexity without reducing them to archetypical templates. These are rich desserts, best enjoyed (I think) in small sittings: on busses, trains, in elevators, waiting rooms, anywhere a reader can occasionally look up, as the last sentences of these pieces so often prompt, and glimpse the underlying wonder of common experience, and be moved to make something of it.